This post is based on the lectures by Daniele Micciancio: Introduction to lattices

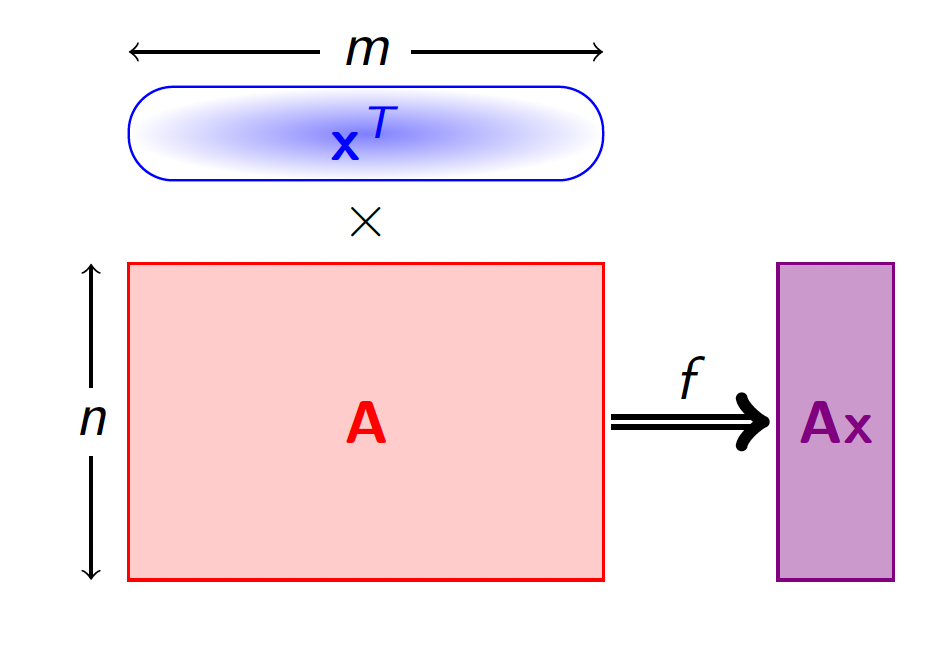

Let’s put parameters $m,n,q \in \mathbb{Z}$ which we describe later. Then, let’s put a uniformly random matrix $A \in \mathbb{Z}_q^{n\times m}$. Next, we put a function $f_A(\mathbf{x})\colon\, \mathbb{Z}_q^m \rightarrow \mathbb{Z}_q^n$ as follows:

\[f_A(\mathbf{x}) = A\mathbf{x} = \mathbf{a}_ix_i\mod{q}.\]

For the matrix $A$ we put an SIS lattice as

\[\Lambda_A = \{\mathbf{x} \in \mathbb{Z}^m \;|\; A\mathbf{x} = \mathbf{0}\} \subset \mathbb{Z}^m.\]We obviously note that $A$ is not a $\Lambda_A$ lattice basis, but the definition above obviously gives us a group which is closed under addition and scalar multiplication, which we thus can understand as a lattice. Moreover, we do not even care about its basis.

The main idea here is that for properly selected parameters, the SVP problem for a lattice $\Lambda_A$ is hard while $A$ is uniformly random. Then, if we modify our $f_A(\mathbf{x})$ as follows

\[f_A(\mathbf{x})\colon\, \{0,1\}^m \rightarrow \mathbb{Z}_q^n,\]then we can use it as a collision-resistant hash function. More precisely, we put

- $n$ — a security parameter;

- $q = n^2 = n^{O(q)}$ — a small modulus;

- $m = 2n\log{q} = O(n\log{n})$.

Then, taking for example $n = 256, q = 2^{16}, m = 8192$ we can understand $f_A$ as a compression function $8192$ to $4096$ bits.

But how from the hardness of the SVP on $\Lambda_A$ follows the hardness of collision search? Imagine we know an effective algorithm to find a collision, i.e., two vectors $\mathbf{x}\neq \mathbf{y} \in {0,1}^m$ such that $A\mathbf{x} = A\mathbf{y}$. Then, by subtraction, we get

\[A(\mathbf{x}-\mathbf{y}) = \mathbf{0},\]where vector $\mathbf{x}-\mathbf{y} \in {-1,0,1}^m$, which means that we found a very good approximate solution to the SVP problem on $\Lambda_A$, which is assumed to be impossible to find. It means that the effective algorithm to find a collision does not exist.

Such functions $f_A$ are called Ajtai’s one-way functions based on the SIS problem. But we still have not answered why it is hard to invert the image. Let’s show why it is hard. One can note that we can represent any vector $\mathbf{a}_i \in A$ as a sum of a lattice $\Lambda_A$ vector and some another vector:

\[\mathbf{a}_i = \mathbf{v}_i + \mathbf{r}_i,\; \mathbf{v}_i \in \Lambda_A.\]It is already proven that we can find such a set of vectors $\mathbf{r}_i$ where for each of them $|r_i| \leq \sqrt{n}\lambda_n$ where $\lambda_n$ is an $n$-th successive minima of the lattice $\Lambda_A$. Then, if there exists an efficient algorithm to find a pre-image of $f_A(\mathbf{x})$, then for $f_A(\mathbf{x}) = \mathbf{0}$, we can find a vector $\mathbf{x} \in {0,1}^m$.

\[\sum \mathbf{a}_i x_i = \sum (\mathbf{v}_i + \mathbf{r}_i)x_i = \mathbf{0}.\]Then

\[\sum \mathbf{v}_i x_i = -\sum \mathbf{r}_i x_i.\]One can note that $|\sum \mathbf{r}_i x_i| \leq |\mathbf{x}|\cdot\max{|\mathbf{r_i}|} \simeq n\lambda_n$. So, the high-level idea is that using such an algorithm, we can also find a small enough lattice $\Lambda_A$ vector, which should be impossible.

One can note that, unfortunately, working with such a matrix $A$ is not efficient due to the storage costs. There exists a technique called Hermite Normal Form (HNF) which reduces the size quite a lot.